- The Laboratory

- Organization

- Departments

- Jobs

- Analysis book

- Contact

- News

- Publications

- Download

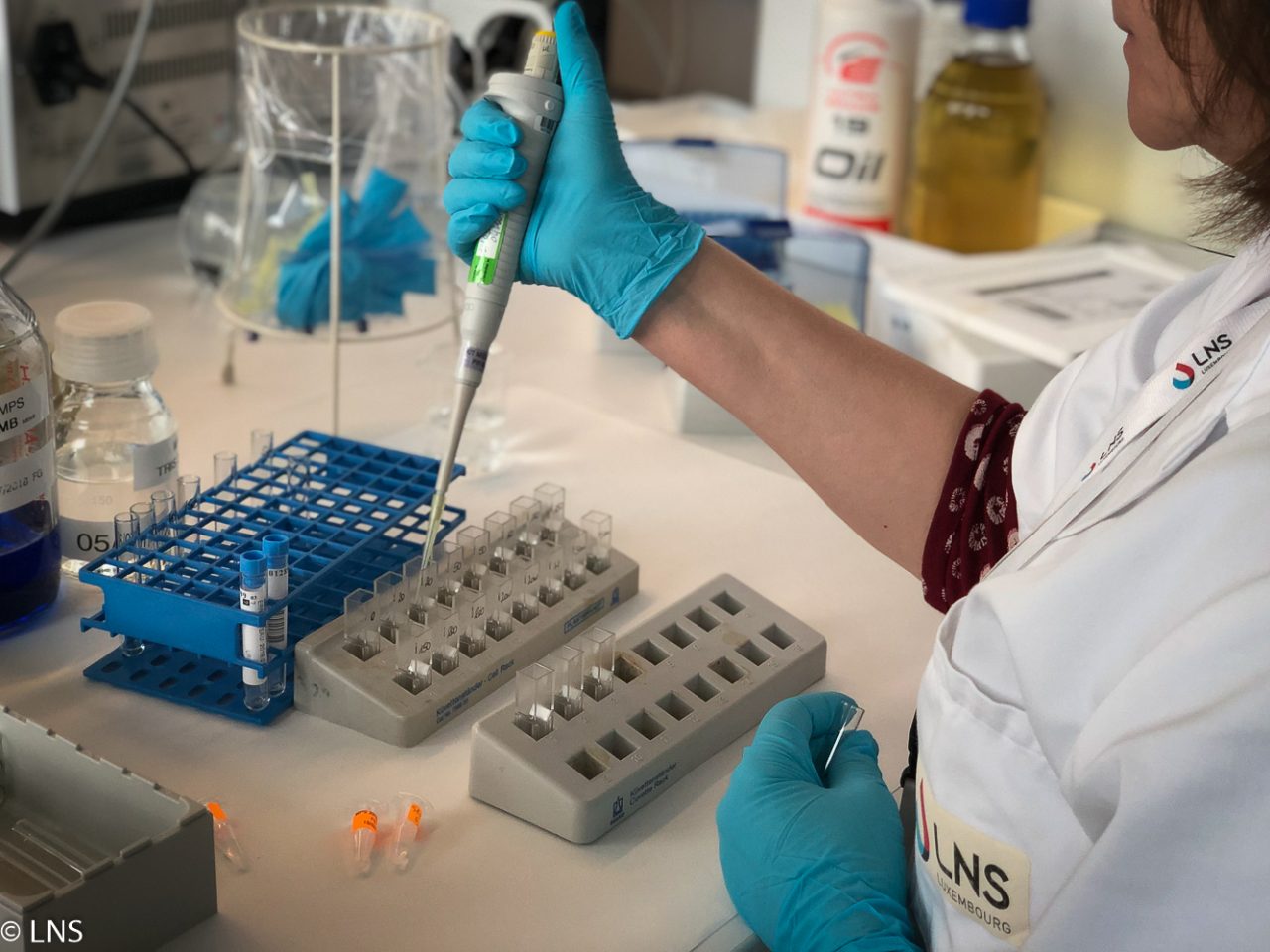

As part of the LNS Annual Report 2018, we conducted a series of interviews and reports to better present the LNS through its staff and departments. This is the seventh interview featuring Dr pharm. Dsc. Patricia Bord, head of the department of medical biology, followed by the corresponding report. Enjoy your discovery!

As part of the LNS Annual Report 2018, we conducted a series of interviews and reports to better present the LNS through its staff and departments. This is the seventh interview featuring Dr pharm. Dsc. Patricia Bord, head of the department of medical biology, followed by the corresponding report. Enjoy your discovery!

The neonatal screening and metabolic diseases unit of the department of medical biology aims to identify babies born with rare diseases, often of genetic origin. The aim is to diagnose these diseases as quickly as possible and apply effective treatment during the first days of life in order to prevent severe deficiencies or even death. So far, the unit has been detecting the following four diseases by using dried whole blood spots: phenylketonuria, congenital hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and medium-chain acyl-coenzime A dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency. On 2 January 2018, it launched a new pilot project under the auspices of the Direction de la Santé: the cystic fibrosis screening for all babies born in Luxembourg.

THE IMPORTANCE OF AN EARLY DIAGNOSIS

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited and incurable disease that causes the body to produce excess mucus that is abnormally thick and sticky; symptoms are usually nutritional disorders and frequent bronchopulmonary infections. Research has shown that children who receive cystic fibrosis care early in life have better health outcomes than those who are diagnosed later. Early diagnosis and treatment improves growth, helps keep lung healthy, reduces hospital stays and adds years to life.

“Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis is slightly different from other programs in the sense that it is carried out in collaboration with the National Center of Genetics and the Luxembourg Centre for Cystic Fibrosis and Related Diseases”, says Dr pharm. DSc Patricia Borde, head of the department. “Screening is done on the same dried blood sample, the Guthrie card, like that used for other diseases, at the same age of the child – i.e., 72 hours of life – and is based on a two-step technique.”

The first step is the measurement of a biomarker, immunoreactive trypsin (IRT), on the blood sample. If the concentration of IRT is out of the normal range and if written parental consent is obtained, the Guthrie card is transferred to the National Center of Genetics for DNA testing. In the absence of written permission, the parents are contacted by the maternity ward and informed of the need to continue the examinations by a second IRT measurement on a second Guthrie card. The genetic test does not cover all the possible mutations of the so called cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene – there are more than 2,000 – but the 50 most frequent are included, which is high number compared to the neighbouring countries.

THE RELEVANCE OF THE SWEAT CHLORIDE TEST

Different situations are possible subsequent to the genetic analyses. If two mutations are identified, the baby must be seen in a specialised centre, the Luxembourg Centre for Cystic Fibrosis and Related Diseases (Centre Luxembourgeois de Mucoviscidose et des Maladies apparentées or CLMMA) at the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg (CHL), to rule out or confirm the diagnosis by a sweat chloride test. This test measures the amount of chloride in the child’s sweat. Chloride is part of the body’s electrolyte balance and combines with sodium to form the salt found in sweat. A colourless and odourless chemical that causes sweating (pilocarpine) is applied to a small area of skin (usually on the arm or leg). An electrode is then placed over the spot to induce sweating. The procedure does not cause any pain at all, only a feeling of warmth in the area. The sweat is collected on a piece of filter paper or gauze or in a plastic coil and sent to the hospital laboratory for evaluation. Children with cystic fibrosis have an elevated level of chloride in their sweat.

If only a single mutation is detected, the child may be a healthy carrier of the disease (as is one of the parents), which is most likely, or the child may have cystic fibrosis. A sweat chloride test at the CHL is also needed in this case. If no mutation is detected, an IRT rate-check is performed on Day 21. If the rate is still above the average, the child must be seen at the CLMMA where investigations will be carried out. In most of these cases, further investigations may make it possible to confirm the diagnosis.

SEVERAL CLINICAL FORMS OF THE DISEASE

“For some children, it may be difficult to establish a firm diagnosis”, specified Dr pharm. DSc Patricia Borde. “The baby may have an intermediate sweat test and does not carry mutations or sometimes one or two particular mutations. The clinical expression of the disease can be highly variable. There is not one but several clinical forms of the disease.”

One year after the launching of the project, Dr pharm. DSc Patricia Borde has come to a positive conclusion. “Of the 7,245 Guthrie cards we received in 2018, we have detected three in which babies are found to have a serious form of cystic fibrosis. That tends to prove that our screening is useful and can make the lives of children with this disease healthier. We are working now to improve the consent form to be signed by the parents. They are sometimes very concerned when they learn that genetic tests may be required for their child. It is important to mention that a high IRT level is not specific to cystic fibrosis. A large number of newborns have hypertrypsinemia without having cystic fibrosis. In addition, genetic testing is restricted to the CFTR gene and not on all the genes of the child. A brochure, written in four languages (English, French, German and Portuguese) will be published in the first quarter of 2019 by the ministère de la Santé to better explain to parents the usefulness and need of this test.”